The American Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865, was a divisive conflict between the Northern Union and the Southern Confederacy, primarily over the expansion of slavery into western territories. The political tension surrounding slavery culminated with the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, leading seven southern states to secede and form the Confederacy. Following Lincoln's victory, the Confederacy quickly seized U.S. forts and federal assets, prompting four more states to secede. Over the next four years, the two sides engaged in fierce combat, primarily in the Southern states.

The turning point for the Union came with Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, which declared freedom for all slaves in rebel states. The Union's strategic victories, including the crucial win at Vicksburg, which split the Confederacy, and the blockade of Confederate ports, crippled the South's efforts. Notable battles included Confederate General Robert E. Lee's northern advance ending at Gettysburg and the Union's capture of Atlanta in 1864. The war's end was signaled by Lee's surrender to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in April 1865.

Despite the official surrender, skirmishes persisted briefly, and the assassination of Lincoln shortly after added to the nation's grief. The war resulted in the devastating loss of between 620,000 and 750,000 soldiers, making it the deadliest conflict in United States history. The aftermath saw the collapse of the Confederacy, the abolition of slavery, and the start of the Reconstruction era, aimed at rebuilding the nation and integrating the former Confederate states. The war's impact, both in terms of its technological advancements and its sheer brutality, set the stage for future global conflicts.

The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 provided that no new slaves were permitted to be imported into the United States. It took effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest date permitted by the United States Constitution. The domestic slave trade within the United States was not affected by the 1807 law. Indeed, with the legal supply of imported slaves terminated, the domestic trade increased in importance.

Slavery was the main cause of disunion. Slavery had been a controversial issue during the framing of the Constitution but had been left unsettled. The issue of slavery had confounded the nation since its inception, and increasingly separated the United States into a slaveholding South and a free North. The issue was exacerbated by the rapid territorial expansion of the country, which repeatedly brought to the fore the issue of whether new territory should be slaveholding or free. The issue had dominated politics for decades leading up to the war. Key attempts to solve the issue included the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850, but these only postponed an inevitable showdown over slavery.

The motivations of the average person were not necessarily those of their faction; [ 1 ] some Northern soldiers were indifferent on the subject of slavery, but a general pattern can be established. [ 2 ] As the war dragged on, more and more Unionists came to support the abolition of slavery, whether on moral grounds or as a means to cripple the Confederacy. [ 3 ] Confederate soldiers fought the war primarily to protect a Southern society of which slavery was an integral part. [ 4 ] Opponents of slavery considered slavery an anachronistic evil incompatible with republicanism. The strategy of the anti-slavery forces was containment—to stop the expansion of slavery and thereby put it on a path to ultimate extinction. [ 5 ] The slaveholding interests in the South denounced this strategy as infringing upon their constitutional rights. [ 6 ] Southern whites believed that the emancipation of slaves would destroy the South's economy, because of the large amount of capital invested in slaves and fears of integrating the ex-slave black population. [ 7 ] In particular, many Southerners feared a repeat of the 1804 Haiti massacre (referred to at the time as "the horrors of Santo Domingo"), [ 8 ] in which former slaves systematically murdered most of what was left of the country's white population—including men, women, children, and even many sympathetic to abolition—after the successful slave revolt in Haiti. Historian Thomas Fleming points to the historical phrase "a disease in the public mind" used by critics of this idea and proposes it contributed to the segregation in the Jim Crow era following emancipation. [ 9 ] These fears were exacerbated by the 1859 attempt of John Brown to instigate an armed slave rebellion in the South. [ 10 ]

Tragic Prelude painting ©John Steuart Curry

1850 Jan 1The concept of manifest destiny intensified the divisive issue of slavery in newly acquired American territories. Between 1803 and 1854, as the U.S. expanded its territories through various means, each new region faced the contentious decision of whether to permit slavery. For a time, territories were balanced equally between slave and free states, but tensions heightened over the territories west of the Mississippi. The aftermath of the Mexican–American War, particularly the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, further inflamed these debates. While some hoped to extend slavery into the new territories, others, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, foresaw that these lands would intensify the conflict over the slavery issue.

By 1860, four dominant doctrines had emerged regarding federal control over territories and the issue of slavery. The first, tied to the Constitutional Union Party, sought to make the division established by the Missouri Compromise a constitutional directive. The second, endorsed by Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans, argued that Congress had the discretion to restrict, but not establish, slavery in territories. The third doctrine, territorial or "popular" sovereignty, championed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, posited that settlers in a territory had the right to decide on slavery. This belief led to the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 and subsequent violent conflicts in "Bleeding Kansas". The final doctrine, propagated by Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis, revolved around state sovereignty or "states' rights", suggesting that states had the right to promote slavery's expansion within the federal union.

The conflict over these doctrines and the expansion of slavery underscored the political rifts leading up to the Civil War. The doctrines each represented different visions for the future of the U.S. and its stance on slavery, highlighting the deep-seated divisions on the issue. As the 1860 presidential election approached, these ideologies represented the core debates surrounding slavery, territories, and the interpretation of the U.S. Constitution.

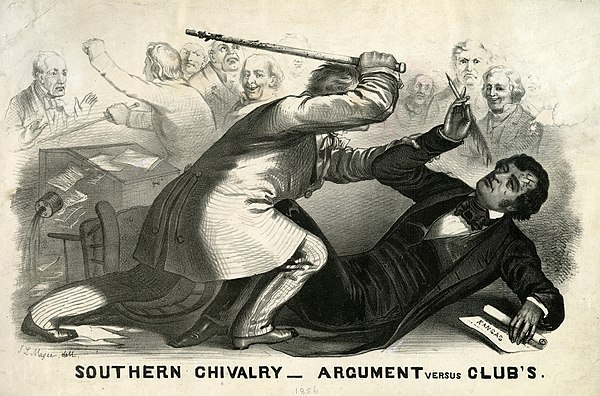

Preston Brooks attacking Charles Sumner in the U.S. Senate in 1856 ©John L. Magee

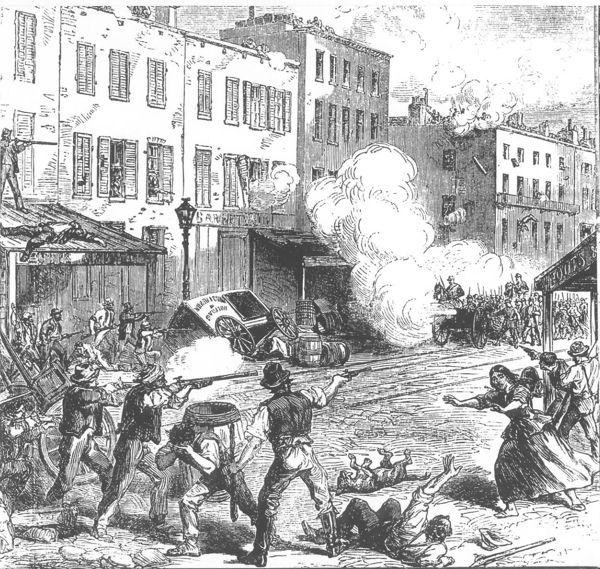

1854 Jan 1 - 1861 JanBleeding Kansas refers to a violent series of events between 1854 and 1859 in the Kansas Territory and western Missouri. Stemming from a heated political and ideological dispute over the fate of slavery in the soon-to-be state of Kansas, the region saw a surge in electoral fraud, assaults, raids, and killings. Proslavery "border ruffians" and antislavery "free-staters" were the primary participants in this conflict, with estimates indicating up to 200 fatalities, [ 11 ] though 56 were documented. [ 12 ] This turmoil is often viewed as a precursor to the American Civil War.

Central to the conflict was the determination of whether Kansas would enter the Union as a slave or free state. This decision held immense significance at the national level, as the entrance of Kansas would tip the balance of power in the U.S. Senate, which was already deeply divided over slavery. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 stipulated that the matter would be settled by popular sovereignty, allowing the territory's settlers to decide. This ignited further tensions, as many proslavery sympathizers from Missouri entered Kansas under false pretenses to sway the vote. The political struggle soon devolved into a full-blown civilian conflict, marked by gang violence and guerrilla warfare. Parallel to this, Kansas experienced its own miniature civil war, complete with dueling capitals, constitutions, and legislatures. Both sides solicited external aid, with U.S. Presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan openly supporting proslavery factions. [ 13 ]

After extensive turmoil and a congressional investigation, it became evident that a majority of Kansans desired a free state. However, Southern representatives in Congress stonewalled this decision until many had left during the secession crisis that precipitated the Civil War. On January 29, 1861, Kansas was officially admitted to the Union as a free state. Even so, the border region continued to witness violence throughout the Civil War. The events of Bleeding Kansas showcased the inevitable nature of the conflict over slavery, highlighting the improbability of resolving sectional disagreements without violence and serving as a grim overture to the larger Civil War. [ 14 ] Today, numerous memorials and historic sites honor this period.

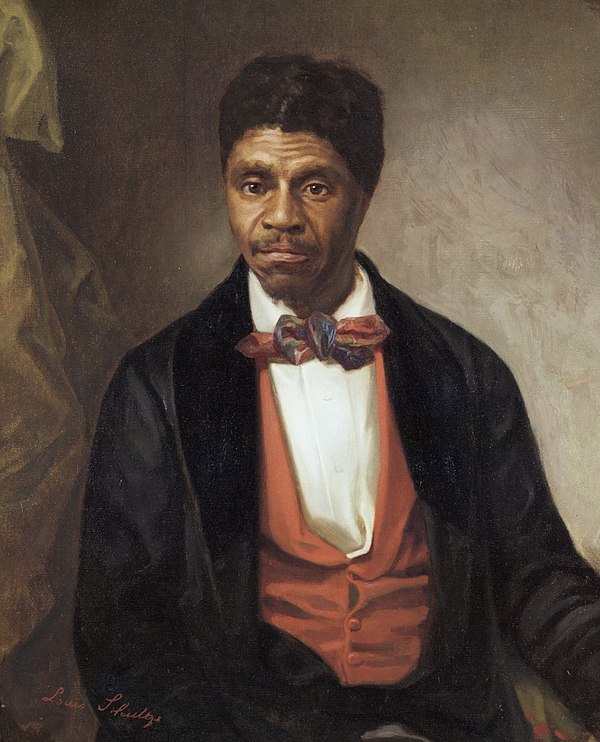

Dred Scott ©Louis Schultze

Dred Scott v. Sandford is recognized as one of the most controversial decisions in U.S. Supreme Court history, determining in 1857 that the Constitution did not recognize people of black African descent as American citizens, thereby denying them the rights and privileges reserved for citizens. [ 15 ] This decision, regarded as one of the Court's most regrettable, centered around Dred Scott, an enslaved black individual who had lived in territories where slavery was illegal. Scott argued that his time in these territories entitled him to freedom. Nevertheless, by a 7–2 verdict, the Supreme Court ruled against him. Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote the majority opinion, asserting that African-descended individuals "were not intended to be included" as citizens in the Constitution, referencing historical laws to argue that a distinct separation was intended between white citizens and those they enslaved. The Court's decision also invalidated the Missouri Compromise, dismissing it as an overreach of Congressional authority regarding property rights of slaveholders. [ 15 ]

The ruling, instead of quelling the growing dispute over slavery, only intensified the national divide on the issue. [ 16 ] While the decision found favor among slaveholding states, it was vehemently opposed in the non-slaveholding states. [ 17 ] The verdict stoked the fires of the national debate on slavery, significantly contributing to the tensions that led to the American Civil War. Just years after the decision, the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution were ratified, respectively abolishing slavery and guaranteeing citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States.

The aftermath of Dred Scott v. Sandford saw its ruling overshadowed by larger political movements and events. Historians largely view the decision as exacerbating the divisions that would culminate in the Civil War. [ 18 ] During the 1860 U.S. elections, the newly-formed Republican Party, advocating abolition, countered the Supreme Court's verdict, suggesting it was influenced by bias and exceeded its jurisdiction. Their candidate, Abraham Lincoln, contested the court's findings and declared he would limit slavery's expansion. Lincoln's election is commonly seen as the trigger for Southern states' secession, marking the onset of the American Civil War. [ 19 ]

Last Moments Of Slavery Abolitionist John Brown ©Thomas Hovenden

From October 16 to 18, 1859, abolitionist John Brown led a raid on the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), intending to spark a widespread slave revolt in the Southern states. This event, considered by some as a precursor to the Civil War, saw Brown and his group of 22 individuals ultimately defeated by U.S. Marines under First Lieutenant Israel Greene's leadership. The aftermath of the raid was significant: ten raiders died in the skirmish, seven faced execution following a trial, and five managed to escape. Notably, prominent figures like Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Jeb Stuart, and John Wilkes Booth had roles or were witnesses to the unfolding events. Brown had even sought the involvement of renowned abolitionists Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, but they did not participate due to illness and skepticism about the raid's feasibility, respectively.

The raid was the first national crisis to benefit from the rapid news dissemination capabilities of the newly invented electrical telegraph. Journalists were quick to reach Harpers Ferry, providing real-time updates on the situation. This immediacy of coverage highlighted the evolving landscape of news reporting. Interestingly, contemporary reports used a variety of terms to describe the event, but "raid" was not among them. Descriptors like "insurrection," "rebellion," and "treason" were more common.

John Brown's audacious act at Harpers Ferry elicited mixed reactions across the U.S. The South perceived it as a direct assault on their way of life and the institution of slavery, while some Northerners viewed it as a courageous stand against oppression. Initial public opinion deemed the raid as the misguided effort of a zealot. However, Brown's eloquence during his trial, combined with the advocacy of supporters like Henry David Thoreau, transformed him into a symbolic figure championing the cause of the Union and the abolition of slavery.

Lincoln's Election ©Hesler

1860 Nov 6The election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 was the final trigger for secession. Efforts at compromise, including the Corwin Amendment and the Crittenden Compromise, failed. Southern leaders feared that Lincoln would stop the expansion of slavery and put it on a course toward extinction. When Lincoln won the presidential election in 1860, the South lost any hope of compromise. Jefferson Davis claimed that all the cotton states would secede from the Union. The Confederacy formed from seven states of the Deep South: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas in January and February 1861. They wrote the Confederate Constitution, which required slavery forever throughout the Confederacy. Until elections were held, Davis was the provisional president. Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861.

Secession and Outbreak

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy from 1861 to 1865 ©Mathew Brady

1861 Feb 8 - 1865 May 9The Confederacy was formed on February 8, 1861 (and exited until May 9, 1865) by seven slave states: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. All seven of the states were located in the Deep South region of the United States, whose economy was heavily dependent upon agriculture—particularly cotton—and a plantation system that relied upon enslaved Africans for labor. Convinced that white supremacy and slavery were threatened by the November 1860 election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln to the U.S. presidency, on a platform which opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories, the Confederacy declared its secession from the United States, with the loyal states becoming known as the Union during the ensuing American Civil War. In the Cornerstone Speech, Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens described its ideology as centrally based "upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.

Bombardment of the Fort by the Confederates ©Anonymous

The American Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter. Fort Sumter is located in the middle of the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. [ 26 ] Its status had been contentious for months. Outgoing President Buchanan had dithered in reinforcing the Union garrison in the harbor, which was under command of Major Robert Anderson. Anderson took matters into his own hands and on December 26, 1860, under the cover of darkness, sailed the garrison from the poorly placed Fort Moultrie to the stalwart island Fort Sumter. [ 27 ] Anderson's actions catapulted him to hero status in the North. An attempt to resupply the fort on January 9, 1861, failed and nearly started the war then and there. But an informal truce held. [ 28 ] On March 5, the newly sworn in Lincoln was informed that the Fort was running low on supplies. [ 29 ]

Fort Sumter proved to be one of the main challenges of the new Lincoln administration. [ 29 ] Back-channel dealing by Secretary of State Seward with the Confederates undermined Lincoln's decision-making; Seward wanted to pull out of the fort. [ 30 ] But a firm hand by Lincoln tamed Seward, and Seward became one of Lincoln's staunchest allies. Lincoln ultimately decided that holding the fort, which would require reinforcing it, was the only workable option. Thus, on April 6, Lincoln informed the Governor of South Carolina that a ship with food but no ammunition would attempt to supply the Fort. Historian McPherson describes this win-win approach as "the first sign of the mastery that would mark Lincoln's presidency"; the Union would win if it could resupply and hold onto the Fort, and the South would be the aggressor if it opened fire on an unarmed ship supplying starving men. [ 31 ] An April 9 Confederate cabinet meeting resulted in President Davis's ordering General P. G. T. Beauregard to take the Fort before supplies could reach it. [ 32 ]

At 4:30 am on April 12, Confederate forces fired the first of 4,000 shells at the Fort; it fell the next day. The loss of Fort Sumter lit a patriotic fire under the North. [ 33 ] On April 15, Lincoln called on the states to field 75,000 volunteer troops for 90 days; impassioned Union states met the quotas quickly. [ 34 ] On May 3, 1861, Lincoln called for an additional 42,000 volunteers for a period of three years. [ 35 ] Shortly after this, Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina seceded and joined the Confederacy. To reward Virginia, the Confederate capital was moved to Richmond. [ 36 ]

"The Battle of Mobile Bay". ©J.B. Elliott

During the American Civil War, the Union implemented the Anaconda Plan under General Winfield Scott, aimed at suffocating the Southern economy to force a Confederate surrender. [ 20 ] Central to this strategy, initiated in April 1861 by President Abraham Lincoln, was a blockade of all Southern ports, which severely restricted the Confederacy's ability to trade, particularly in cotton—its economic backbone. [ 21 ]

The blockade dramatically reduced the South's capacity to export cotton, with exports plummeting to less than 10% of pre-war levels. Major ports like New Orleans, Mobile, and Charleston were particularly affected. By June 1861, Union warships were deployed off key Southern ports, and the fleet expanded to nearly 300 ships by the following year. [ 22 ] This blockade was critical in isolating the Confederacy and hindering its war effort. The Confederacy subsequently looked to foreign sources for their enormous military needs and sought out financiers and companies like S. Isaac, Campbell & Company and the London Armoury Company in Britain, who acted as purchasing agents for the Confederacy, connecting them with Britain's many arms manufactures, and ultimately becoming the Confederacy's main source of arms. [ 23 ]

To counter the blockade, the Confederacy relied on blockade runners, small, fast ships designed to evade Union naval forces. These vessels were primarily constructed in Britain and operated routes through Bermuda, Cuba, and the Bahamas, trading imported arms and supplies for cotton. Many of the ships were lightweight and designed for speed and could only carry a relatively small amount of cotton back to England. [ 24 ] Despite some success, many of these ships were captured by the Union, with their cargoes sold as prizes of war. When the Union Navy seized a blockade runner, the ship and cargo were condemned as a prize of war and sold, with the proceeds given to the Navy sailors; the captured crewmen were mostly British, and they were released. [ 25 ]

The Southern economy was near collapse during the war, exacerbated by the blockade which curtailed imports of critical goods and crippled the coastal trade. Although blockade runners did manage to import vital supplies, including 400,000 rifles, the blockade's overall effectiveness was significant, contributing heavily to the economic strangulation of the Confederacy. The blockade not only cut off essential supplies but also led to widespread shortages and economic disarray within the Confederate states.

Additionally, the war period saw significant changes in global commodities, notably the rise of oil. The decline of the whale oil industry, accelerated by the war and Confederate disruptions of Union whaling, led to increased reliance on kerosene and other oil products. This shift marked the beginning of oil's prominence as a major commodity.

The strategic blockade, therefore, played a pivotal role in undermining the Confederate war effort, leading to significant economic hardship and contributing to the eventual Union victory. After the war, the impact of these strategies continued to resonate, shaping economic and diplomatic relations, as evidenced by Britain's compensation to the United States for damages caused by raiders outfitted in British ports.

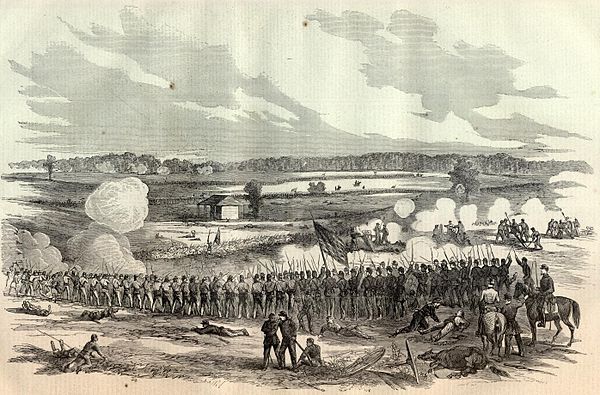

First Battle of Bull Run. ©Kurz & Allison

Just months after the start of the war at Fort Sumter, the Northern public clamored for a march against the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, which was expected to bring an early end to the Confederacy. Yielding to political pressure, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell led his unseasoned Union Army across Bull Run against the equally inexperienced Confederate Army of Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard camped near Manassas Junction. McDowell's ambitious plan for a surprise flank attack on the Confederate left was poorly executed; nevertheless, the Confederates, who had been planning to attack the Union left flank, found themselves at an initial disadvantage.

Confederate reinforcements under Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston arrived from the Shenandoah Valley by railroad, and the course of the battle quickly changed. A brigade of Virginians under a relatively unknown brigadier general from the Virginia Military Institute, Thomas J. Jackson, stood its ground, which resulted in Jackson receiving his famous nickname, "Stonewall". The Confederates launched a strong counterattack, and as the Union troops began withdrawing under fire, many panicked and the retreat turned into a rout. McDowell's men frantically ran without order in the direction of Washington, D.C.

Both armies were sobered by the fierce fighting and the many casualties and realized that the war was going to be much longer and bloodier than either had anticipated. The First Battle of Bull Run highlighted many of the problems and deficiencies that were typical of the first year of the war. Units were committed piecemeal, attacks were frontal, infantry failed to protect exposed artillery, tactical intelligence was minimal, and neither commander was able to employ his whole force effectively. McDowell, with 35,000 men, could commit only about 18,000, and the combined Confederate forces, with about 32,000 men, also committed 18,000. [ 37 ]

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas (the name used by Confederate forces), was the first major battle of the American Civil War.

Fort Hatteras surrenders ©Forbes Waud Taylor

1861 Aug 28 - Aug 29The Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries (August 28–29, 1861) was the first combined operation of the Union Army and Navy in the American Civil War, resulting in Union domination of the strategically important North Carolina Sounds. Two forts on the Outer Banks, Fort Clark and Fort Hatteras, had been built by the Confederates to protect their commerce-raiding activity. These were lightly defended, however, and their artillery could not engage the bombarding fleet under Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham, commandant of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which had been ordered to keep moving, to avoid presenting a static target. Although held up by bad weather, the fleet was able to land troops under General Benjamin Butler, who took the surrender of Flag Officer Samuel Barron.

This battle represented the first application of the naval blockading strategy. The Union retained both forts, providing valuable access to the sounds, and commerce raiding was much reduced. The victory was welcomed by a demoralized Northern public after the humiliating First Battle of Bull Run. The engagement is sometimes known as the Battle of Forts Hatteras and Clark.

Trent Affair ©Edward Sylvester Ellis

On November 8, 1861, USS San Jacinto, commanded by Union Captain Charles Wilkes, intercepted the British mail packet RMS Trent and removed, as contraband of war, two Confederate envoys: James Murray Mason and John Slidell. The envoys were bound for Britain and France to press the Confederacy's case for diplomatic recognition and to lobby for possible financial and military support.

Public reaction in the United States was to celebrate the capture and rally against Britain, threatening war. In the Confederate states, the hope was that the incident would lead to a permanent rupture in Anglo-American relations and possibly even war, or at least diplomatic recognition by Britain. Confederates realized their independence potentially depended on intervention by Britain and France. In Britain, there was widespread disapproval of this violation of neutral rights and insult to their national honor. The British government demanded an apology and the release of the prisoners and took steps to strengthen its military forces in British North America and the North Atlantic.

President Abraham Lincoln and his top advisors did not want to risk war with Britain over this issue. After several tense weeks, the crisis was resolved when the Lincoln administration released the envoys and disavowed Captain Wilkes's actions, although without a formal apology. Mason and Slidell resumed their voyage to Europe.

Eastern and Western Theaters

Battle of Mill Springs ©Larry Selman

In late 1861, Confederate Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer guarded Cumberland Gap, the eastern end of a defensive line extending from Columbus, Kentucky. In November he advanced west into Kentucky to strengthen control in the area around Somerset and made Mill Springs his winter quarters, taking advantage of a strong defensive position. Union Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas, ordered to break up the army of Maj. Gen. George B. Crittenden (Zollicoffer's superior), sought to drive the Confederates across the Cumberland River. His force arrived at Logan's Crossroads on January 17, 1862, where he waited for Brig. Gen. Albin Schoepf's troops from Somerset to join him. The Confederate force under Crittenden attacked Thomas at Logan's Crossroads at dawn on January 19. Unbeknownst to the Confederates, some of Schoepf's troops had arrived as reinforcements. The Confederates achieved early success, but Union resistance rallied and Zollicoffer was killed. A second Confederate attack was repulsed. Union counterattacks on the Confederate right and left were successful, forcing them from the field in a retreat that ended in Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Mill Springs was the first significant Union victory of the war, much celebrated in the popular press, but was soon eclipsed by Ulysses S. Grant's victories at Forts Henry and Donelson.

The Union gunboat attack on Fort Henry, sketched by Alexander Simplot for Harper's Weekly ©Harper's Weekly

In early 1861 the critical border state of Kentucky had declared neutrality in the American Civil War. This neutrality was first violated on September 3, when Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, acting on orders from Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, occupied Columbus, Kentucky. The riverside town was situated on 180 foot high bluffs that commanded the river at that point, where the Confederates installed 140 large guns, underwater mines and a heavy chain that stretched a mile across the Mississippi River to Belmont, while occupying the town with 17,000 Confederate troops, thus cutting off northern commerce to the south and beyond.

Two days later, Union Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, displaying the personal initiative that would characterize his later career, seized Paducah, Kentucky, a major transportation hub of rail and port facilities at the mouth of the Tennessee River. Henceforth, neither adversary respected Kentucky's proclaimed neutrality, and the Confederate advantage was lost. The buffer zone that Kentucky provided between the North and the South was no longer available to assist in the defense of Tennessee.

On February 4 and 5, Grant landed two divisions just north of Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. (The troops serving under Grant were the nucleus of the Union's successful Army of the Tennessee, although that name was not yet in use.) Grant's plan was to advance upon the fort on February 6 while it was being simultaneously attacked by Union gunboats commanded by Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote. A combination of accurate and effective naval gunfire, heavy rain, and the poor siting of the fort, nearly inundated by rising river waters, caused its commander, Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman, to surrender to Foote before the Union Army arrived.

The surrender of Fort Henry opened the Tennessee River to Union traffic south of the Alabama border. In the days following the fort's surrender, from February 6 through February 12, Union raids used ironclad boats to destroy Confederate shipping and railroad bridges along the river. On February 12, Grant's army proceeded overland 12 miles (19 km) to engage with Confederate troops in the Battle of Fort Donelson.

Battle of Fort Donelson ©Johnston, William Preston

Following his capture of Fort Henry on February 6, Grant moved his army (later to become the Union's Army of the Tennessee) 12 miles (19 km) overland to Fort Donelson, from February 11 to 13, and conducted several small probing attacks. On February 14, Union gunboats under Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote attempted to reduce the fort with gunfire, but were forced to withdraw after sustaining heavy damage from the fort's water batteries.

On February 15, with the fort surrounded, the Confederates, commanded by Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd, launched a surprise attack, led by his second-in-command, Brig. Gen. Gideon Johnson Pillow, against the right flank of Grant's army. The intention was to open an escape route for retreat to Nashville, Tennessee. Grant was away from the battlefield at the start of the attack, but arrived to rally his men and counterattack. Pillow's attack succeeded in opening the route, but Floyd lost his nerve and ordered his men back to the fort. The following morning, Floyd and Pillow escaped with a small detachment of troops, relinquishing command to Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, who accepted Grant's demand of unconditional surrender later that evening. The battle resulted in virtually all of Kentucky as well as much of Tennessee, including Nashville, falling under Union control. The capture opened the Cumberland River, an important avenue for the invasion of the South. It elevated Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant from an obscure and largely unproven leader to the rank of major general, and earned him the nickname of "Unconditional Surrender" Grant.

Bombardment and Capture of Island Number Ten on the Mississippi River, April 7, 1862. ©Official U.S. Navy Photograph

Island Number Ten, a small island at the base of a tight double turn in the river, was held by the Confederates from the early days of the war. It was an excellent site to impede Union efforts to invade the South by the river, as ships had to approach the island bows on and then slow to make the turns. For the defenders, however, it had an innate weakness in that it depended on a single road for supplies and reinforcements. If an enemy force managed to cut that road, the garrison would be isolated and eventually be forced to surrender.

Union forces began the siege in March 1862, shortly after the Confederate Army abandoned their position at Columbus, Kentucky. The Union Army of the Mississippi under Brigadier General John Pope made the first probes, coming overland through Missouri and occupying the town of Point Pleasant, Missouri, almost directly west of the island and south of New Madrid. Two days after the fall of New Madrid, Union gunboats and mortar rafts sailed downstream to attack Island No. 10. Over the next three weeks, the island's defenders and forces in the nearby supporting batteries were subjected to a steady bombardment by the flotilla, mostly carried out by the mortars.

Pope persuaded Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote to send a gunboat past the batteries, to assist him in crossing the river by keeping off any Southern gunboats and suppressing Confederate artillery fire at the point of attack. The USS Carondelet, under Commander Henry Walke, slipped past the island on the night of April 4, 1862. This was followed by the USS Pittsburg, under Lieutenant Egbert Thompson two nights later. With the support of these two gunboats, Pope was able to move his army across the river and trap the Confederates opposite the island, who by now were trying to retreat. Outnumbered at least three to one, the Confederates realized their situation was hopeless and decided to surrender. At about the same time, the garrison on the island surrendered to Flag Officer Foote and the Union flotilla.

The Union victory marked the first time the Confederate Army lost a position on the Mississippi River in battle. The river was now open to the Union Navy as far as Fort Pillow, a short distance above Memphis. Only three weeks later, New Orleans fell to a Union fleet led by David G. Farragut, and the Confederacy was in danger of being cut in two along the line of the river.

The Peninsula Campaign. ©Donna Neary

The Peninsula campaign (also known as the Peninsular campaign) of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, was an amphibious turning movement against the Confederate States Army in Northern Virginia, intended to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. McClellan was initially successful against the equally cautious General Joseph E. Johnston, but the emergence of the more aggressive General Robert E. Lee turned the subsequent Seven Days Battles into a humiliating Union defeat.

McClellan landed his army at Fort Monroe and moved northwest, up the Virginia Peninsula. Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Magruder's defensive position on the Warwick Line caught McClellan by surprise. His hopes for a quick advance foiled, McClellan ordered his army to prepare for a siege of Yorktown. Just before the siege preparations were completed, the Confederates, now under the direct command of Johnston, began a withdrawal toward Richmond. The first heavy fighting of the campaign occurred in the Battle of Williamsburg, in which the Union troops managed some tactical victories, but the Confederates continued their withdrawal. An amphibious flanking movement to Eltham's Landing was ineffective in cutting off the Confederate retreat. In the Battle of Drewry's Bluff, an attempt by the U.S. Navy to reach Richmond by way of the James River was repulsed.

As McClellan's army reached the outskirts of Richmond, a minor battle occurred at Hanover Court House, but it was followed by a surprise attack by Johnston at the Battle of Seven Pines or Fair Oaks. The battle was inconclusive, with heavy casualties, but it had lasting effects on the campaign. Johnston was wounded by a Union artillery shell fragment on May 31 and replaced the next day by the more aggressive Robert E. Lee, who reorganized his army and prepared for offensive action in the final battles of June 25 to July 1, which are popularly known as the Seven Days Battles. The end result was that the Union army was unable to enter Richmond, and both armies remained intact.

Jackson's Valley campaign ©Keith Rocco

Jackson's Valley campaign, also known as the Shenandoah Valley campaign of 1862, was Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's spring 1862 campaign through the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia during the American Civil War. Employing audacity and rapid, unpredictable movements on interior lines, Jackson's 17,000 men marched 646 miles (1,040 km) in 48 days and won several minor battles as they successfully engaged three Union armies (52,000 men), preventing them from reinforcing the Union offensive against Richmond.

Jackson followed up his successful campaign by forced marches to join Gen. Robert E. Lee for the Seven Days Battles outside Richmond. His audacious campaign elevated him to the position of the most famous general in the Confederacy (until this reputation was later supplanted by Lee) and has been studied ever since by military organizations around the world.

Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas. ©Kurz and Allison

The Battle of Pea Ridge (March 7–8, 1862), also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, took place during the American Civil War near Leetown, northeast of Fayetteville, Arkansas. Federal forces, led by Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, moved south from central Missouri, driving Confederate forces into northwestern Arkansas. Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn had launched a Confederate counteroffensive, hoping to recapture northern Arkansas and Missouri. Confederate forces met at Bentonville and became the most substantial Rebel force, by way of guns and men, to assemble in the Trans-Mississippi. Against odds Curtis held off the Confederate attack on the first day and drove Van Dorn's force off the battlefield on the second. By defeating the Confederates, the Union forces established Federal control of most of Missouri and northern Arkansas.

First Battle of Iron Ships of War ©Louis Prang & Co

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the Monitor and Merrimack (rebuilt and renamed as the CSS Virginia) or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over two days, March 8–9, 1862, in Hampton Roads, a roadstead in Virginia where the Elizabeth and Nansemond rivers meet the James River just before it enters Chesapeake Bay adjacent to the city of Norfolk. The battle was a part of the effort of the Confederacy to break the Union blockade, which had cut off Virginia's largest cities and major industrial centers, Norfolk and Richmond, from international trade. [ 38 ] At least one historian has argued that the Confederacy, rather than trying to break the blockade, was simply trying to take complete control of Hampton Roads in order to protect Norfolk and Richmond. [ 39 ]

This battle has major significance because it was the first meeting in combat of ironclad warships, USS Monitor and CSS Virginia. The Confederate fleet consisted of the ironclad ram Virginia (built from the remnants of the burned steam frigate USS Merrimack, newest warship for the United States Navy / Union Navy) and several supporting vessels. On the first day of battle, they were opposed by several conventional, wooden-hulled ships of the Union Navy.

The battle received worldwide attention, and it had immediate effects on navies around the world. The preeminent naval powers, Great Britain and France, halted further construction of wooden-hulled ships, and others followed suit. Although Britain and France had been engaged in an iron-clad arms race since the 1830s, the Battle of Hampton Roads signaled a new age of naval warfare had arrived for the whole world. [ 40 ] A new type of warship, monitor, was produced on the principle of the original. The use of a small number of very heavy guns, mounted so that they could fire in all directions, was first demonstrated by Monitor but soon became standard in warships of all types. Shipbuilders also incorporated rams into the designs of warship hulls for the rest of the century. [ 41 ]

First Battle of Kernstown ©Keith Rocco

Attempting to tie down the Union forces in the Valley, under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, Jackson received incorrect intelligence that a small detachment under Col. Nathan Kimball was vulnerable, but it was in fact a full infantry division more than twice the size of Jackson's force. His initial cavalry attack was forced back and he immediately reinforced it with a small infantry brigade. With his other two brigades, Jackson sought to envelop the Union right by way of Sandy Ridge. But Col. Erastus B. Tyler's brigade countered this movement, and, when Kimball's brigade moved to his assistance, the Confederates were driven from the field. There was no effective Union pursuit.

Although the battle was a Confederate tactical defeat, it represented a strategic victory for the South by preventing the Union from transferring forces from the Shenandoah Valley to reinforce the Peninsula Campaign against the Confederate capital, Richmond. Following the earlier Battle of Hoke's Run, the First Battle of Kernstown may be considered the second among Jackson's rare defeats.

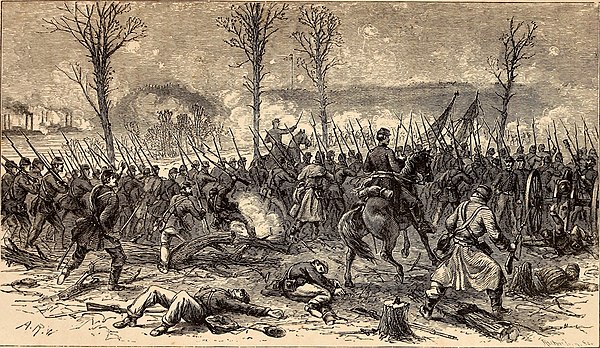

The Battle of Shiloh. ©Thulstrup

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the American Civil War fought on April 6–7, 1862. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield is located between a small, undistinguished church named Shiloh and Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. Two Union armies combined to defeat the Confederate Army of Mississippi. Major General Ulysses S. Grant was the Union commander, while General Albert Sidney Johnston was the Confederate commander until his battlefield death, when he was replaced by his second-in-command, General P. G. T. Beauregard.

The Confederate army hoped to defeat Grant's Army of the Tennessee before it could be reinforced and resupplied. Although it made considerable gains with a surprise attack during the first day of the battle, Johnston was mortally wounded and Grant's army was not eliminated. Overnight, Grant's Army of the Tennessee was reinforced by one of its divisions stationed farther north, and was also joined by portions of the Army of the Ohio, under the command of Major General Don Carlos Buell. The Union forces conducted an unexpected counterattack in the morning, which reversed the Confederate gains of the previous day. The exhausted Confederate army withdrew further south, and a modest Union pursuit started and ended on the next day.

Though victorious, the Union army had more casualties than the Confederates, and Grant was heavily criticized. Decisions made on the battlefield by leadership on both sides were questioned, often by those who were not present for the fighting. The battle was the costliest engagement of the Civil War up to that point, and its nearly 24,000 casualties made it one of the bloodiest battles in the entire war.

Admiral Farragut's second division passes the forts. ©J.O. Davidson

The Union's strategy was devised by Winfield Scott, whose "Anaconda Plan" called for the division of the Confederacy by seizing control of the Mississippi River. One of the first steps in such operations was the imposition of the Union blockade. After the blockade was established, a Confederate naval counterattack attempted to drive off the Union navy, resulting in the Battle of the Head of Passes. The Union countermove was to enter the mouth of the Mississippi River, ascend to New Orleans and capture the city, closing off the mouth of the Mississippi to Confederate shipping both from the Gulf and from Mississippi River ports still used by Confederate vessels. In mid-January 1862, Flag Officer David G. Farragut had undertaken this enterprise with his West Gulf Blockading Squadron. The way was soon open except the water passage past the two masonry forts held by Confederate artillery, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, which were above the Head of Passes approximately 70 miles (110 km) downriver below New Orleans.

The two Confederate forts on the Mississippi River south of the city were attacked by a Union Navy fleet. As long as the forts could keep the Federal forces from moving on the city, it was safe, but if they fell or were bypassed, there were no fall-back positions to impede the Union advance.

New Orleans, the largest city in the Confederacy, was already under threat of attack from its north when David Farragut moved his fleet into the river from the south. Although the Union threat from upriver was geographically more remote than that from the Gulf of Mexico, a series of losses in Kentucky and Tennessee had forced the Confederate War and Navy Departments in Richmond to strip the region of much of its defenses. Men and equipment had been withdrawn from the local defenses, so that by mid-April almost nothing remained south of the city except the two forts and an assortment of gunboats of questionable worth. [ 42 ] Without reducing the pressure from the north, (Union) President Abraham Lincoln set in motion a combined Army-Navy operation to attack from the south. The Union Army offered 18,000 soldiers, led by the political general Benjamin F. Butler. The Navy contributed a large fraction of its West Gulf Blockading Squadron, which was commanded by Flag Officer David G. Farragut. The squadron was augmented by a semi-autonomous flotilla of mortar schooners and their support vessels under Commander David Dixon Porter. [ 43 ]

The ensuing battle can be divided into two parts: a mostly-ineffective bombardment of the Confederate-held forts by the raft-mounted mortars, and the successful passage of the forts by much of Farragut's fleet on the night of April 24. During the passage, one Federal warship was lost and three others turned back, while the Confederate gunboats were virtually obliterated. The subsequent capture of the city, achieved with no further significant opposition, was a serious, even fatal, blow from which the Confederacy never recovered. [ 44 ] The forts remained after the fleet had passed, but the demoralized enlisted men in Fort Jackson mutinied and forced their surrender. [ 45 ]

Farragut's flagship, USS Hartford, forces its way past Fort Jackson. ©Julian Oliver Davidson

1862 Apr 25 - May 1The Capture of New Orleans was a significant naval and military campaign during the American Civil War that took place in late April 1862. It was a major Union victory, led by Flag Officer David G. Farragut, which enabled the Union forces to gain control of the Mississippi River's mouth and effectively seal off the key Southern port.

The operation began when Farragut led an assault past the Confederate defenses of Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip. Despite facing heavy fire and obstacles like chains and floating torpedoes (mines), Farragut's fleet managed to bypass the forts, moving upriver and reaching the city of New Orleans. There, the city's defenses proved inadequate, and its leaders realized they could not resist the Union fleet's firepower, leading to a relatively quick surrender.

The capture of New Orleans had substantial strategic implications. It not only closed off a vital Confederate trade route but also set the stage for the Union's control of the entire Mississippi River, a crucial blow to the Confederate war effort. The event was also significant for boosting Northern morale and demonstrated the vulnerability of the Confederate coastline.

Battle of McDowell ©Don Troiani

After suffering a tactical defeat at the First Battle of Kernstown, Jackson withdrew to the southern Shenandoah Valley. Union forces commanded by Brigadier Generals Robert Milroy and Robert C. Schenck were advancing from what is now West Virginia towards the Shenandoah Valley. After being reinforced by troops commanded by Brigadier General Edward Johnson, Jackson advanced towards Milroy and Schenck's encampment at McDowell. Jackson quickly took the prominent heights of Sitlington's Hill, and Union attempts to recapture the hill failed. The Union forces retreated that night, and Jackson pursued, only to return to McDowell on 13 May. After McDowell, Jackson defeated Union forces at several other battles during his Valley campaign.

Battle of Front Royal ©Don Troiani

After defeating Major General John C. Frémont's force in the Battle of McDowell, Jackson turned against the forces of Major General Nathaniel Banks. Banks had most of his force at Strasburg, Virginia, with smaller detachments at Winchester and Front Royal. Jackson attacked the position at Front Royal on May 23, surprising the Union defenders, who were led by Colonel John Reese Kenly. Kenly's men made a stand on Richardson's Hill and used artillery fire to hold off the Confederates, before their line of escape over the South Fork and North Fork of the Shenandoah River was threatened. The Union troops then withdrew across both forks to Guard Hill, where they made a stand until Confederate troops were able to get across the North Fork. Kenly made one last stand at Cedarville, but an attack by 250 Confederate cavalrymen shattered the Union position. Many of the Union soldiers were captured, but Banks was able to withdraw his main force to Winchester. Two days later, Jackson then drove Banks out of Winchester, and won two further victories in June. Jackson's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley had tied down 60,000 Union troops from joining the Peninsula campaign, and his men were able to join Robert E. Lee's Confederate force in time for the Seven Days battles.

First Battle of Winchester ©Don Troiani

Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks learned on May 24, 1862, that the Confederates had captured his garrison at Front Royal, Virginia, and were closing on Winchester, turning his position. He ordered a hasty retreat down the Valley Pike from Strasburg. Banks deployed at Winchester to slow the Confederate pursuit. Jackson enveloped the right flank of the Union Army under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks and pursued it as it fled across the Potomac River into Maryland. Jackson's success in achieving force concentration early in the fighting allowed him to secure a more decisive victory which had escaped him in previous battles of the campaign. First Winchester was a major victory in Jackson's Valley Campaign, both tactically and strategically. Union plans for the Peninsula Campaign, an offensive against Richmond, were disrupted by Jackson's audacity, and thousands of Union reinforcements were diverted to the Valley and the defense of Washington, D.C.

New York and Massachusetts men slam into the flank of Law's Brigade at the Battle of Seven Pines, May 31, 1862. ©William Trego

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, nearby Sandston, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of an offensive up the Virginia Peninsula by Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, in which the Army of the Potomac reached the outskirts of Richmond.

On May 31, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston attempted to overwhelm two Federal corps that appeared isolated south of the Chickahominy River. The Confederate assaults, although not well coordinated, succeeded in driving back the IV Corps and inflicting heavy casualties. Reinforcements arrived, and both sides fed more and more troops into the action. Supported by the III Corps and Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick's division of Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner's II Corps (which crossed the rain-swollen river on Grapevine Bridge), the Federal position was finally stabilized. Gen. Johnston was seriously wounded during the action, and command of the Confederate army devolved temporarily to Maj. Gen. G.W. Smith. On June 1, the Confederates renewed their assaults against the Federals, who had brought up more reinforcements, but made little headway. Both sides claimed victory.

Although the battle was tactically inconclusive, it was the largest battle in the Eastern Theater up to that time (and second only to Shiloh in terms of casualties thus far, about 11,000 total). Gen. Johnston's injury also had profound influence on the war: it led to the appointment of Robert E. Lee as Confederate commander. The more aggressive Lee initiated the Seven Days Battles, leading to a Union retreat in late June. [ 46 ] Seven Pines therefore marked the closest Union forces came to Richmond in this offensive.

The Total Annihilation of the Rebel Fleet by the Federal Fleet under Commodore Davis. ©Anonymous

The First Battle of Memphis was a naval battle fought on the Mississippi River immediately North of the city of Memphis, Tennessee on June 6, 1862, during the American Civil War. The engagement was witnessed by many of the citizens of Memphis. It resulted in a crushing defeat for the Confederate forces, and marked the virtual eradication of a Confederate naval presence on the river. The river was now open down to that city, which was already besieged by Farragut's ships, but the federal army authorities did not grasp the strategic importance of the fact for nearly another six months. Not until November 1862 would the Union Army under Ulysses S. Grant attempt to complete the opening of the river.

Battle of Cross Keys ©Keith Rocco

The hamlet of Port Republic, Virginia, lies on a neck of land between the North and South Rivers, which conjoin to form the South Fork Shenandoah River. On June 6–7, 1862, Jackson's army, numbering about 16,000, bivouacked north of Port Republic, Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell's division along the banks of Mill Creek near Goods Mill, and Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder's division on the north bank of North River near the bridge. The 15th Alabama Infantry regiment was left to block the roads at Union Church. Jackson's headquarters were in Madison Hall at Port Republic. The army trains were parked nearby.

Two Union columns converged on Jackson's position. The army of Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, about 15,000 strong, moved south on the Valley Pike and reached the vicinity of Harrisonburg on June 6. The division of Brig. Gen. James Shields, about 10,000, advanced south from Front Royal in the Luray (Page) Valley, but was badly strung out because of the muddy Luray Road. At Port Republic, Jackson possessed the last intact bridge on the North River and the fords on the South River by which Frémont and Shields could unite. Jackson determined to check Frémont's advance at Mill Creek, while meeting Shields on the east bank of the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. A Confederate signal station on Massanutten monitored Union progress. The Confederate forces (5,800-strong) under John C. Frémont successfully defended their position and repulsed the attack of the Union forces (11,500-strong) under Richard S. Ewell, forcing Frémont to retreat with his forces.

Battle of Port Republic. ©Adam Hook

Jackson learned at 7 a.m. that the Federals were approaching his column. Without proper reconnaissance or waiting for the bulk of his force to come up, he ordered Winder's Stonewall Brigade to charge through the thinning fog. The brigade was caught between artillery on its flank and rifle volleys to its front and fell back in disarray. They had run into two brigades at the vanguard of Shields's army, 3,000 men under Brig. Gen. Erastus B. Tyler. Attempting to extricate himself from a potential disaster, Jackson realized that the Union artillery fire was coming from a spur of the Blue Ridge. Jackson and Winder sent the 2nd and 4th Virginia Infantry regiments through the thick underbrush up the hill, where they encountered three Union infantry regiments supporting the artillery and were repulsed.

After his assault on the Coaling failed, Jackson ordered the rest of Ewell's division, primarily Trimble's brigade, to cross over the North River bridge and burn it behind them, keeping Frémont's men isolated to the north of the River. While he waited for these troops to arrive, Jackson reinforced his line with the 7th Louisiana Infantry of Taylor's brigade and ordered Taylor to make another attempt against the Union batteries. Winder perceived that the Federals were about to attack, so he ordered a preemptive charge, but in the face of point-blank volleys and running low on ammunition, the Stonewall Brigade was routed. At this point, Ewell arrived on the battlefield and ordered the 44th and 58th Virginia Infantry regiments to strike the left flank of the advancing Union battle line. Tyler's men fell back, but reorganized and drove Ewell's men into the forest south of the Coaling.

Taylor attacked the infantry and artillery on the Coaling three times before prevailing, but having achieved their objective, were faced by a new charge from three Ohio regiments. It was only the surprise appearance by Ewell's troops that convinced Tyler to withdraw his men. The Confederates began bombarding the Union troops on the flat lands, with Ewell himself gleefully manning one of the cannons. More Confederate reinforcements began to arrive, including the brigade of Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro, and the Union army reluctantly began to withdraw. Jackson remarked to Ewell, "General, he who does not see the hand of God in this is blind, sir, blind."

The impetuosity of Jackson had betrayed him into attacking before his troops were sufficiently massed, which was made difficult by the insufficient means of crossing the river. The Battle of Port Republic had been poorly managed by Jackson and was the most damaging to the Confederates in terms of casualties—816 against a force one half his size (about 6,000 to 3,500). Union casualties were 1,002, with a high percentage representing prisoners. After the dual defeats at Cross Keys and Port Republic, the Union armies retreated, leaving Jackson in control of the upper and middle Shenandoah Valley and freeing his army to reinforce Robert E. Lee before Richmond in the Seven Days Battles.

Seven Days Battles ©Mort Künstler

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, away from Richmond and into a retreat down the Virginia Peninsula. The series of battles is sometimes known erroneously as the Seven Days Campaign, but it was actually the culmination of the Peninsula Campaign, not a separate campaign in its own right.

The Seven Days began on Wednesday, June 25, 1862, with a Union attack in the minor Battle of Oak Grove, but McClellan quickly lost the initiative as Lee began a series of attacks at Beaver Dam Creek (Mechanicsville) on June 26, Gaines's Mill on June 27, the minor actions at Garnett's and Golding's Farm on June 27 and 28, and the attack on the Union rear guard at Savage's Station on June 29. McClellan's Army of the Potomac continued its retreat toward the safety of Harrison's Landing on the James River. Lee's final opportunity to intercept the Union Army was at the Battle of Glendale on June 30, but poorly executed orders and the delay of Stonewall Jackson's troops allowed his enemy to escape to a strong defensive position on Malvern Hill. At the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, Lee launched futile frontal assaults and suffered heavy casualties in the face of strong infantry and artillery defenses.

The Seven Days ended with McClellan's army in relative safety next to the James River, having suffered almost 16,000 casualties during the retreat. Lee's army, which had been on the offensive during the Seven Days, lost over 20,000. As Lee became convinced that McClellan would not resume his threat against Richmond, he moved north for the northern Virginia campaign and the Maryland campaign.

Battle of Oak Grove ©Thure Tulstrup

Following the stalemate at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31 and June 1, 1862, McClellan's Army of the Potomac sat passively in their positions around the eastern outskirts of Richmond. The new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, General Robert E. Lee, used the following three and a half weeks to reorganize his army, extend his defensive lines, and plan offensive operations against McClellan's larger army. McClellan received intelligence that Lee was prepared to move and that the arrival of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's force from the Shenandoah Valley was imminent.

McClellan decided to resume the offensive before Lee could. Anticipating Jackson's reinforcements marching from the north, he increased cavalry patrols on likely avenues of approach. He wanted to advance his siege artillery about a mile and a half closer to the city by taking the high ground on Nine Mile Road around Old Tavern. In preparation for that, he planned an attack on Oak Grove, south of Old Tavern and the Richmond and York River Railroad, which would position his men to attack Old Tavern from two directions. Known locally for a stand of tall oak trees, Oak Grove was the site of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill's assault at Seven Pines on May 31 and had seen numerous clashes between pickets since that time.

The attack was planned to advance to the west, along the axis of the Williamsburg Road, in the direction of Richmond. Between the two armies was a small, dense forest, 1,200 yards (1,100 m) wide, bisected by the headwaters of White Oak Swamp. Two divisions of the III Corps were selected for the assault, commanded by Brig. Gens. Joseph Hooker and Philip Kearny. Facing them was the division of Confederate Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger.

The Battle of Oak Grove took place on June 25, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, the first of the Seven Days Battles (Peninsula Campaign) of the American Civil War. Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan advanced his lines with the objective of bringing Richmond within range of his siege guns. Two Union divisions of the III Corps attacked across the headwaters of White Oak Swamp, but were repulsed by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger's Confederate division. McClellan, who was 3 miles (4.8 km) in the rear, initially telegraphed to call off the attack, but ordered another attack over the same ground when he arrived at the front. Darkness halted the fighting. Union troops gained only 600 yards (550 m), at a cost of over a thousand casualties on both sides.

Battle of Mechanicsville ©Keith Rocco

The Union Army straddled the rain-swollen Chickahominy River. Four of the Army's five corps were arrayed in a semicircular line south of the river. The V Corps under Brig. Gen. Porter was north of the river near Mechanicsville in an L-shaped line running north–south behind Beaver Dam Creek and southeast along the Chickahominy. Lee moved most of his army north of the Chickahominy to attack the Union north flank. This concentrated about 65,000 troops against 30,000, leaving only 25,000 to protect Richmond against the other 60,000 men of the Union army. It was a risky plan that required careful execution, but Lee knew that he could not win in a battle of attrition or siege against the Union army. The Confederate cavalry under Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart had reconnoitered Porter's right flank as part of a daring circumnavigation of the entire Union army from June 12 to June 15 and found it vulnerable. Stuart's forces burned a couple of Union supply ships and was able to report much of McClellan's army's strength and position to Gen. Lee. McClellan was aware of Jackson's arrival and presence at Ashland Station, but did nothing to reinforce Porter's vulnerable corps north of the river.

Lee's plan called for Jackson to begin the attack on Porter's north flank early on June 26. Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill's Light Division was to advance from Meadow Bridge when he heard Jackson's guns, clear the Union pickets from Mechanicsville, and then move to Beaver Dam Creek. The divisions of Maj. Gens. D.H. Hill and James Longstreet were to pass through Mechanicsville, D.H. Hill to support Jackson and Longstreet to support A.P. Hill. Lee expected Jackson's flanking movement to force Porter to abandon his line behind the creek, and so A. P. Hill and Longstreet would not have to attack Union entrenchments. South of the Chickahominy, Magruder and Huger were to demonstrate, deceiving the four Union corps on their front.

The Battle of Beaver Dam Creek, also known as the Battle of Mechanicsville, took place on June 26, 1862, in Hanover County, Virginia, was the first major engagement of the Seven Days Battles during the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the start of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's counter-offensive against the Union Army of the Potomac, under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, which threatened the Confederate capital of Richmond. Lee attempted to turn the Union right flank, north of the Chickahominy River, with troops under Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, but Jackson failed to arrive on time. Instead, Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill threw his division, reinforced by one of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill's brigades, into a series of futile assaults against Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corps, which occupied defensive works behind Beaver Dam Creek. Confederate attacks were driven back with heavy casualties. Porter withdrew his corps safely to Gaines Mill, with the exception of Company F (a.k.a. The Hopewell Rifles) of the 8th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment who did not receive the orders to retreat.

Battle of Garnett's & Golding's Farm ©Steve Noon

While the battle at Gaines's Mill raged north of the Chickahominy River, the forces of Confederate general John B. Magruder conducted a reconnaissance in force that developed into a minor attack against the Union line south of the river at Garnett's Farm. The Confederates attacked again near Golding's Farm on the morning of June 28 but in both cases were easily repulsed. The action at the Garnett and Golding farms accomplished little beyond convincing McClellan that he was being attacked from both sides of the Chickahominy.

Battle of Gaines' Mill ©Don Troiani

Following the inconclusive Battle of Beaver Dam Creek (Mechanicsville) the previous day, Confederate General Robert E. Lee renewed his attacks against the right flank of the Union Army, relatively isolated on the northern side of the Chickahominy River. There, Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corps had established a strong defensive line behind Boatswain's Swamp. Lee's force was destined to launch the largest Confederate attack of the war, about 57,000 men in six divisions. Porter's reinforced V Corps held fast for the afternoon as the Confederates attacked in a disjointed manner, first with the division of Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill, then Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, suffering heavy casualties. The arrival of Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson's command was delayed, preventing the full concentration of Confederate force before Porter received some reinforcements from the VI Corps.

At dusk, the Confederates finally mounted a coordinated assault that broke Porter's line and drove his men back toward the Chickahominy River. The Federals retreated across the river during the night. The Confederates were too disorganized to pursue the main Union force. Gaines' Mill saved Richmond for the Confederacy in 1862; the tactical defeat there convinced Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan to abandon his advance on Richmond and begin a retreat to the James River. The battle occurred in almost the same location as the Battle of Cold Harbor nearly two years later.

Battle of Savage's Station ©Anonymous

The Army of the Potomac continued its retreat toward the James River. The bulk of McClellan's army concentrated around Savage's Station on the Richmond and York River Railroad, preparing for a difficult crossing through and around White Oak Swamp. It did so without centralized direction because McClellan had personally moved south of Malvern Hill after Gaines' Mill without leaving directions for corps movements during the retreat nor naming a second in command. Clouds of black smoke filled the air as the Union troops were ordered to burn anything they could not carry. Union morale plummeted, particularly so for those wounded, who realized that they were not being evacuated from Savage's Station with the rest of the Army.

Lee devised a complex plan to pursue and destroy McClellan's army. While the divisions of Maj. Gens. James Longstreet and A.P. Hill looped back toward Richmond and then southeast to the crossroads at Glendale, and Maj. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes's division headed farther south, to the vicinity of Malvern Hill, Brig. Gen. John B. Magruder's division was ordered to move due east along the Williamsburg Road and the York River Railroad to attack the Federal rear guard. Stonewall Jackson, commanding his own division, as well as the divisions of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill and Brig. Gen. William H. C. Whiting, was to rebuild a bridge over the Chickahominy and head due south to Savage's Station, where he would link up with Magruder and deliver a strong blow that might cause the Union Army to turn around and fight during its retreat. Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Magruder pursued along the railroad and the Williamsburg Road and struck Maj. Gen. Edwin Vose Sumner's II Corps (the Union rearguard) with three brigades near Savage's Station, while Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's divisions were stalled north of the Chickahominy River. Union forces continued to withdraw across White Oak Swamp, abandoning supplies and more than 2,500 wounded soldiers in a field hospital.

Confederate troops charging Randol's battery. ©Allen C. Redwood

General Robert E. Lee ordered his Confederate divisions of the Army of Northern Virginia, under the field command of Major Generals Benjamin Huger, James Longstreet, and A.P. Hill, to converge upon Union Major General George B. McClellan's retreating Army of the Potomac in transit in the vicinity of Glendale (or Frayser's Farm), attempting to catch it in the flank and destroy it in detail. The Army of the Potomac was moving out of the White Oak Swamp on a retreat from the Chickahominy River to the James River following the perceived defeat at the Battle of Gaines' Mill; as the Union Army approached the Glendale crossroad, it was forced to turn southward with its right flank exposed to the west. Lee's goal was to thrust a multi-pronged attack of his divisions into the Army of the Potomac near the Glendale crossroad, where a vanguard of Union defenders was caught largely unaware.

The coordinated assault envisioned by Lee failed to materialize due to difficulties encountered by Huger and un-spirited efforts made by Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, but successful attacks made by Longstreet and Hill near the Glendale crossroad penetrated the Union defenses near Willis Church and temporarily breached the line. Union counterattacks sealed the breach and turned the Confederates back, repulsing their attack upon the line of retreat along the Willis Church/Quaker Road through brutal close-quarters hand-to-hand fighting. North of Glendale, Huger's advance was stopped on the Charles City Road. Near the White Oak Swamp Bridge, the divisions led by Jackson were simultaneously delayed by Union Brigadier General William B. Franklin's corps at White Oak Swamp. South of Glendale near Malvern Hill, Confederate Major General Theophilus H. Holmes made a feeble attempt to attack the Union left flank at Turkey Bridge but was driven back.

The battle was Lee's best chance to cut off the Union Army from the safety of the James River, and his efforts to bisect the Federal line failed. The Army of the Potomac successfully retreated to the James, and that night, the Union army established a strong position on Malvern Hill.

A watercolor of the Battle of Malvern Hill. ©Robert Sneden

The Union's V Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter, took up positions on the hill on June 30. McClellan was not present for the initial exchanges of the battle, having boarded the ironclad USS Galena and sailed down the James River to inspect Harrison's Landing, where he intended to locate the base for his army. Confederate preparations were hindered by several mishaps. Bad maps and faulty guides caused Confederate Maj. Gen. John Magruder to be late for the battle, an excess of caution delayed Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger, and Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson had problems collecting the Confederate artillery.

The battle occurred in stages: an initial exchange of artillery fire, a minor charge by Confederate Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead, and three successive waves of Confederate infantry charges triggered by unclear orders from Lee and the actions of Maj. Gens. Magruder and D. H. Hill, respectively. In each phase, the effectiveness of the Federal artillery was the deciding factor, repulsing attack after attack, resulting in a tactical Union victory. In the course of four hours, a series of blunders in planning and communication had caused Lee's forces to launch three failed frontal infantry assaults across hundreds of yards of open ground, unsupported by Confederate artillery, charging toward firmly entrenched Union infantry and artillery defenses. These errors provided Union forces with an opportunity to inflict heavy casualties.

Despite the Union army's victory, the battle did little to alter the outcome of the Peninsula Campaign: after the battle, McClellan and his forces withdrew from Malvern Hill to Harrison's Landing, where he remained until August 16. His plan to capture Richmond had been thwarted. The Confederate press heralded Lee as the savior of Richmond. In stark contrast, McClellan was accused of being absent from the battlefield, a harsh criticism that haunted him when he ran for president in 1864.

Black Union troops of Company E during the American Civil War. ©Anonymous

The Militia Act of 1862 (12 Stat. 597, enacted July 17, 1862) was an Act of the 37th United States Congress, during the American Civil War, that authorized a militia draft within a state when the state could not meet its quota with volunteers. The Act, for the first time, also allowed African-Americans to serve in the militias as soldiers and war laborers. The act was controversial. It was praised by many abolitionists as a first step toward equality, because it stipulated that black recruits could be soldiers or manual laborers. However, the Act enacted discrimination in pay and other areas. It provided that most black soldiers were to receive $10 a month, with a $3 reduction for clothing, which was almost half as was received by white soldiers who received $13.

The state-administered system set up by the Act failed in practice and in 1863 Congress passed the Enrollment Act, the first genuine national conscription law. The 1863 law required the enrollment of every male citizen and those immigrants who had filed for citizenship between ages 20 and 45 and making them liable for conscription.

Battle of Cedar Mountain - Jackson Is With You! ©Don Troiani

Union forces under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks attacked Confederate forces under Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson near Cedar Mountain as the Confederates marched on Culpeper Court House to forestall a Union advance into central Virginia. After nearly being driven from the field in the early part of the battle, a Confederate counterattack broke the Union lines resulting in a Confederate victory. The battle was the first combat of the Northern Virginia campaign.

Kentucky Campaign ©Mort Küntsler

1862 Aug 14 - Oct 10The Confederate Heartland Offensive (August 14 – October 10, 1862), also known as the Kentucky Campaign, was an American Civil War campaign conducted by the Confederate States Army in Tennessee and Kentucky where Generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith tried to draw neutral Kentucky into the Confederacy by outflanking Union troops under Major General Don Carlos Buell. Though they scored some successes, notably a tactical win at Perryville, they soon retreated, leaving Kentucky primarily under Union control for the rest of the war.

From August 28-30, 1862, the Second Battle of Manassas (Bull Run) took place in Prince William County, Virginia.The battle between General Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate troops and General Pope’s ©Don Troiani

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia against Union Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia, and a battle of much larger scale and numbers than the First Battle of Bull Run (or First Manassas) fought on July 21, 1861 on the same ground.

Following a wide-ranging flanking march, Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson captured the Union supply depot at Manassas Junction, threatening Pope's line of communications with Washington, D.C. Withdrawing a few miles to the northwest, Jackson took up strong concealed defensive positions on Stony Ridge and awaited the arrival of the wing of Lee's army commanded by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet. On August 28, 1862, Jackson attacked a Union column just east of Gainesville, at Brawner's Farm, resulting in a stalemate but successfully getting Pope's attention. On that same day, Longstreet broke through light Union resistance in the Battle of Thoroughfare Gap and approached the battlefield.

Pope became convinced that he had trapped Jackson and concentrated the bulk of his army against him. On August 29, Pope launched a series of assaults against Jackson's position along an unfinished railroad grade. The attacks were repulsed with heavy casualties on both sides. At noon, Longstreet arrived on the field from Thoroughfare Gap and took position on Jackson's right flank. On August 30, Pope renewed his attacks, seemingly unaware that Longstreet was on the field. When massed Confederate artillery devastated a Union assault by Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corps, Longstreet's wing of 25,000 men in five divisions counterattacked in the largest simultaneous mass assault of the war. The Union left flank was crushed and the army was driven back to Bull Run. Only an effective Union rear guard action prevented a replay of the First Manassas defeat. Pope's retreat to Centreville was nonetheless precipitous.

Success in this battle emboldened Lee to initiate the ensuing Maryland Campaign, the South's invasion of the North.

Battle of Richmond ©Dale Gallon